Self-confessed ‘micro-infamous’ Hugo Schwyzer on how he has turned his life around

It’s a gloriously perfect summer day in Hermosa Beach. The temperature hovers around 80 degrees. I’m sitting at a small outdoor table at a Starbucks in an oddly-shaped strip mall diagonally opposite a Trader Joe’s store. A sea breeze wafts by, and if you squint just so, you can see the hazy blue ocean in the distance across the Pacific Coast Highway.

An unassuming, middle-aged man in beige shorts and a royal blue T-shirt saunters up. He’s sporting a fire-engine red Trader Joe’s plastic tag with his name printed simply in white caps: HUGO.

Yet there’s nothing simple about the man in question. Trader Joe’s Hugo is the former Pasadena City College (PCC) gender studies professor Hugo Schwyzer, who in August 2013 engineered his own demise by imploding spectacularly on Twitter.

Diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder, the tenured professor, married father of two and self-described male feminist who also had multiple articles published in national publications, went off his medication and sent out more than 100 tweets in the span of an hour. There, he blurted out shocking confessions including having sex with students and porn stars, calling himself a fraud when it came to teaching gender studies (because his doctorate is in British medieval history), and detailing his life of sexual promiscuity, substance abuse and attempting to kill his then-girlfriend and himself in 1998.

The fallout was quick and epic. Two months later he would be arrested, charged and convicted of felony driving under the influence with special circumstances of causing injury to another person.

Eight years later, Schwyzer is now working at Trader Joe’s (he’s been with the company for 4 1/2 years).

Fresh off his shift, the 54-year-old grabs a coffee from inside and pulls up a chair. His cobalt-blue eyes seem magnified behind his square, black-rimmed glasses. He speaks matter-of-factly but in soft tones. It’s as though eight years of reflection has left him with a sense of calm. The only indication that he may be nervous throughout our 90-minute conversation is the constant removal of the cardboard sleeve from his coffee cup, which he turns and turns again, sliding it in and out of his paper cup as if on an endless loop.

We’re here to talk about teshuvah (redemption). Specifically, his. On his terms.

Schwyzer recently posted on Facebook that he’d been trying to reach the media outlets that had covered his downfall, to ask them to take down those stories. If that wasn’t possible, he hoped they’d write a new story. About where he is now. About how he is no longer that person. About how he deserves a second chance.

His motivation? His children, whom he will cite multiple times throughout the interview.

Schwyzer has a 12-year-old daughter and a 9-year-old son with his fourth ex-wife, with whom he has joint custody. The impetus for speaking out now came from his daughter, who recently started Googling her own name. Inevitably she stumbled across what had been written about him. “It was devastating for her,” he says, adding that some of her school friends began teasing her, “and she asked, ‘Isn’t there anything good written about you on the internet?’ ”

Dozens of well-meaning friends on his Facebook page praised his “brave” decision to try to have something “good” written about him, while others warned that attempting to wade back into the media spotlight could backfire on his offspring. Nevertheless, Schwyzer said the children’s mother and his new fiancée (they have been together for 4 1/2 years and will marry later this year) approved his decision and felt it was the right one for the children.

“I will not recite a formula of contrition in which I do not believe. I do not believe it would make a difference if I did; in the modern era, even if I wept and gnashed my teeth and made the sincerest of apologies, no one would hire me to teach again.”

He says were it not for them, he would accept what had happened to him, as “necessary penance to live with the consequences and occasionally be the subject of ridicule. But I am speaking as a father and not a philosopher. And I recognize that this is a personal plea.”

He qualifies the statement by saying it’s “not about the right to be forgotten. It’s the right to return to a status quo ante, in essence, the same right to rebuild your life that your parents would have had. I’m talking about 30 years ago when you couldn’t Google this stuff.”

But that raises the question: Wouldn’t it be better to just let his children see him for the man he is today and judge him on his current actions?

“Well, I based my decision on not having much else to lose,” he says. “If you read the L.A. Magazine piece, I think it’s an extraordinarily irresponsible piece because (my) mental illness and heavy medication almost disappears (from the story). At one point (the reporter) mentioned I have all these meds lined up but she never questions the veracity of what I’m saying based on the medication.”

He says he signed a release for his psychiatrist to talk to the reporter. “She never even called. She wasn’t interested in that. Even though it was an accurate piece, it wasn’t a fair piece. It wasn’t the complete story.”

Schwyzer believes his complete story should be heard at this point in time because “I think that one of the things about micro-infamy — and I often describe myself as being micro-infamous — is that you become frozen in time based upon a single period or a single incident. In the case of very famous people who have a fall from grace or make a terrible mistake, there is a tremendous amount that’s already known about them so you can put it in context.”

He cites former President Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky, stating that beyond that event, so much more is known about Clinton, and that “highlight or lowlight was just one story among many [about them].”

“I know there is something divine and powerful in the Torah. I feel like a cousin [to Judaism]. A cousin who’s not quite in the family but not quite out of the family.”

And that, he says, is different from someone like him: “People who are in this state of micro-infamy in modern cancel culture. Someone who might have been what I was, which was a college professor slash part-time pundit and journalist well enough known that when my fall happened, it was widely covered. But since then there’s been no follow-up story. So all of my life is frozen in 2013 in terms of Google results.”

Schwyzer believes his follow-up story is one that encompasses teshuvah. To be clear, he has his own definition of what that means. Toward the end of 2020, he began to write posts on Substack. He says he chose Substack “because they don’t participate in SEO (Search Engine Optimization). It is very hard to find someone there. Substack is designed for people who want to — in my case — have some friends give me a little bit of money, which I often think is out of pity or affection. And then I send [my posts] out on Facebook to my friends but I don’t try and promote it that much because I don’t want to poke the bear.”

In his March 29 post titled “Repentance and Return: What Jewish Tradition Tells Us about Restoring the Cancelled,” Schwyzer wrote, ‘I made the decision two years ago that I would consciously reject the kind of restoration plan (for teshuvah) the Jewish community holds forth. … I will not recite a formula of contrition in which I do not believe. I do not believe it would make a difference if I did; in the modern era, even if I wept and gnashed my teeth and made the sincerest of apologies, no one would hire me to teach again. It’s far too great a liability — and as my colleague put it, other people deserve their first shot before I get my second (or, to be frank, my 89th).’

“Depending on the day,” he tells me, “that makes me very angry. And on other days I accept it.”

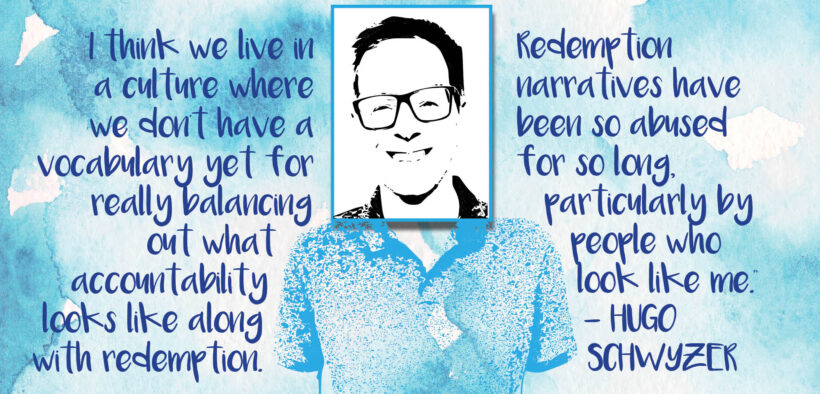

Hugo Schwyzer

Given Schwyzer’s complex relationship with a variety of religions, it’s not surprising that he has created his own definition of teshuvah. His mother’s family is not Jewish, and although his father’s side of the family was, Schwyzer’s grandparents converted to Catholicism in Austria in the 1920s before his father was born. “This was well before the rise of the Nazis,” he says, “but there was enough rising antisemitism for them to see this as (a good decision) professionally.” And Schwyzer’s father wasn’t told he was Jewish until he was in his 20s.

Schwyzer’s fourth wife was also Catholic but became drawn to the Kabbalah Centre in Los Angeles. “She went hardcore kosher, shomrei Shabbat, wore the wig, the whole thing,” he says. Their children attended the Kabbalah Centre. Their son underwent a brit of conversion and their daughter was bat mitzvah this year.

He admits to having dabbled in a variety of religions but says these days “Judaism is certainly closer to me than Christianity. I don’t feel any particular kinship for Jesus anymore. I thought I did when I was younger. Ethically, I feel much closer to Judaism. I don’t know that I believe in God but I do believe in ethical principles.”

Around 2011, Schwyzer may or may not have believed in God when he was studying to become an Orthodox Jew, noting he was a few weeks away from going to the beit din (Jewish court of law) for his conversion but then walked away at the 11th hour. He says this has been a pattern in him since childhood, and something he attributes to his diagnosis of having borderline personality disorder. “I just thought it would be cool to walk away at the last minute.” He says when he used to be a hiker, he would do the same thing. “Nothing could be cooler than climbing a mountain and then stopping 20 feet from the summit.”

He explains that the thinking behind this stems from a notion of “I’m so cool. I don’t need that. I can stop anytime.” He calls it “willfulness” and a kind of “grandiosity” — a word he will employ multiple times throughout our conversation to explain how it is his Achilles’ heel and because of it, it’s a good thing that he will never be allowed to teach again.

So what acts of contrition does he believe he has performed that make him worthy of an article his children can be proud of? That requires sewing together the threads of what happened to him after his public breakdown.

In November 2013, Schwyzer checked into rehab in Malibu, where he would spend the next five weeks. “It was to deal with a dual diagnosis: mental illness and a prescription pill addiction.”

He confesses to being suicidal, thereby explaining his reasons for resigning from his tenured position at PCC. “I didn’t mind resigning at the time because in the back of my head I thought, ‘I’m going to kill myself.’ I was just trying to build up the courage. I had a life insurance policy that I’d already checked with, and it would pay out even in the event of a suicide. So my children would be taken care of and I wouldn’t have to deal with any of this shame.”

While he admits he jumped before he was pushed from the college, he believes “it would have been tough to push me with tenure.” His argument? “I’m the only person that I know of whose entire downfall came as a result of what he claimed. Not one student has ever come forward. There are no accusations against me.”

He says he could at any moment have said, “I’m being delusional and self-destructive. I’ve made this up. And the college would have been really in a fix because knowing what I knew about the young women involved, they would not have talked. So they couldn’t fire me without evidence; without an accusation. Nobody has ever come forward and accused me of anything.”

Did he make it all up?

“No,” he states emphatically. “I’ve thought many times since then about saying that, because one of the features of borderline personality disorder is an extraordinary grandiosity or at least moments of grandiosity. And I thought, ‘How much self-loathing would you have to have to completely invent a story about yourself in order to lose everything as a way of punishing yourself and then stick with it and follow through with it?’ ”

“Teshuvah is humbling oneself not out of self-hatred, but in order to survive, and in order to crush the ego that got you into trouble in the first place. So if nothing else, at least I can say I’m not doing any more harm.”

By December 2013, Schwyzer says he had weaned himself off all the medication he had been placed on in rehab and had moved into a halfway house in Culver City, where he stayed for the next three months. Weaning himself off the medication, he explains, was essential for him to be able to move forward.

“The thing about medication,” he posits, “is it both enables and encourages self-destructive behavior but it prevents the worst self-destructive behavior. It knocks down the suicidal stuff, the ideation but allows you to engage in a lot of other things, including doing a much less healthy version of what I’m doing now, which is the garrulous confessions to journalists. So I get sober and I realize I need to pull my life together.”

His first stop on his road to redemption was heading back to the Kabbalah Centre, where he says he felt “steady. They reminded me that having affairs and telling lies about it is quite biblical. They told me, ‘There are plenty of better people than you [that] have done it. Just pull yourself together and you can come home.’ ”

With that blessing, Schwyzer returned to the Centre and studying Torah. “I know there is something divine and powerful in the Torah,” he says. “I feel like a cousin [to Judaism]. A cousin who’s not quite in the family but not quite out of the family.”

He then worked at a variety of jobs including a stint in an accounting firm before landing at Trader Joe’s. These days he also earns a little bit of money ghost writing. “They all know about my past and I sign NDAs.”

He confesses that “it was and still is a long road. One thing that has been true since December 2013 till now is that I’m committed to living. I can’t leave my children. You have to stay and do the next right thing.” That, for Schwyzer, includes embodying the quote from Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers): “You are not obligated to complete the work but neither are you free to desist.”

“You are not in charge of how you rebuild your life,” he explains. “There’s only so much you can do. You burned so many bridges, but there’s a new bridge that you can start to build. So make the best of what you can with the time you have. And that’s been basically what I’ve done. And I won’t say that I’ve always been cheerful about that.”

He argues when it comes to redemption “people want a very tidy narrative, especially Christians. You know, ‘I once was lost, now I’m found, was blind but now I see.’ Well, you’re blind and then you see, and then you’re blind again. And there have been times when I’ve thought, ‘Maybe I can get a teaching job back. I deserve one. This was unfair. And I’ve thought about playing the (I made it all up) card.”

But, he adds, “that would be bull—-. Because I would be living the lie on the inside and when the #MeToo movement happened in the fall of 2017, I realized that as a white man in his 50s with my track record, there is not any hiring committee that would offer me a job because it’s a colossal liability. We are in a liability-averse age with good reason.”

Teshuvah for Schwyzer is “living as ethical and simple life as I can. And by simple, I mean transparent — where the outsides match the insides. As much as I hate to admit it, that means a life away from teaching, away from punditry, because put a microphone in front of me and I will feel something rise in me that is intoxicating and it will lead me to believe that I can do almost anything.”

Teshuvah for him also is “being bossed around by someone who is 22 years old who is my manager. It’s him saying, ‘Can you go fill the grocery bags?’ and I say, ‘Sure.’ Teshuvah is humbling oneself not out of self-hatred, but in order to survive, and in order to crush the ego that got you into trouble in the first place. So if nothing else, at least I can say I’m not doing any more harm.”

Now I think part of teshuvah is saying — and I’m quoting a Catholic here, St. Francis — my job is to try and understand rather than be understood. And if I’m misrepresented, so be it.”

He says he now understands he cannot be both a college professor with a byline in the Atlantic and occasional gigs on CNN and stay grounded. “Teshuvah is [me saying] ‘If I can’t do both, if I have these liabilities, this mental illness, this addiction to validation, I’m going to limit myself deliberately so that my deep satisfaction comes from taking care of my loved ones.”

Family is one thing, but what of all the people he hurt eight years ago?

In that same March Substack article, Schwyzer wrote, “While I grieve my infidelities and the harm I caused Eira (his ex-wife) and my children, I do not believe that consensual sexual relationships between professors and their adult students are inherently unethical and inevitably harmful.”

Indeed, he says in this interview that what led to him being forced out of PCC was that “I violated a policy, which I wrote forbidding romantic relationships with professors and their students.” A policy he doesn’t believe in.

He goes on to reference Alcoholics Anonymous, in which “they talk a lot about making direct amends to the people you’ve hurt. And there are a lot of people that I’ve been able to make amends to. Then there are other people who don’t want to talk to me. Ultimately, I am not in charge. That’s their story. I can’t tell their story for them. I can’t write their story for them.”

And yet, there is a part of Schwyzer that appears to still harbor resentment for the way his life has unfolded over the past eight years.

“I think we live in a culture where we don’t have a vocabulary yet for really balancing out what accountability looks like along with redemption,” he says. “Redemption narratives have been so abused for so long, particularly by people who look like me — men saying, ‘Baby, I’ve changed. I’m not who I used to be.’ And it turned out not to be true. I think we’ve gotten to a point where we were just utterly fed up, and maybe rightly so. The culture is fed up with bad behavior; particularly the bad behavior of a certain type of white man.”

He says “cancel culture is real” and that he thinks it’s “ridiculous. But I also think that the lack of accountability was ridiculous for a very long time. And I’m enough of a trained historian, even though I schlep groceries now, to know that these things go in cycles and in a few years, there’s going to be a reassessment. And some people will get redeemed and some won’t.”

History, he adds, “is a river. I’ve just got to sit on my raft and ride it as best I can and not rail against it. And I think this may be the wrong thing to be saying to the person who wants to write about me, but I spent so much time on my Substack asking to be understood. But now I think part of teshuvah is saying — and I’m quoting a Catholic here, St. Francis — my job is to try and understand rather than be understood. And if I’m misrepresented, so be it.”

It’s why, he says, on some level he does accept that his past will always follow him. However, Trader Joe’s doesn’t care as long as he does his job. Six months after he landed the gig, he says some people wrote a letter campaign trying to get him fired.

“I’m not clear what they thought that I was going to do in my capacity bagging groceries,” he quips. “That I was somehow mentoring young women? I guess they were worried about my female co-workers. Who knows?”

Trader Joe’s, he says, believes in second chances as long as you back it up with your work. “I’ve been a loyal employee. I get good reviews and am reasonably well liked. I’m on firm ground. And thanks to promotions, I make the princely sum of $18.95 an hour, which is above minimum wage in this town even though that’s not a living wage here. I have health insurance, which I’m also able to provide to my children, and that’s worth a great deal.”

These days, he is in therapy and on a conventional antidepressant, rather than on lithium, which he took for years because he was diagnosed as bipolar. “My current psychiatrist actually does not believe I’m bipolar,” he says. “He believes that I have a severe case of borderline personality disorder … and that describes and really captures that cocktail of where it’s possible to be empathetic narcissistic, grandiose, self-effacing all within 15 minutes.”

We talk about the recent Twitter thread released by Amanda Knox, the American student who spent four years in an Italian prison after being wrongly convicted of murdering her roommate. In that thread, Knox posits the question of who owns her name and her life story?

“Amanda Knox was innocent. I’m stuck being no different than a Larry Nassar (the doctor who treated the U.S. women’s national gymnastics team and was accused of sexually assaulting scores of minors and is now in prison) or (disgraced film mogul) Harvey Weinstein,” Schwyzer says. “I’m not as innocent a victim as Amanda Knox, but I’m not Larry Nassar or Harvey Weinstein. I’m a complicated middle in a time that doesn’t want to look at complicated middles.

“But,” he says with a sigh, “I’ve still gotta bag the groceries, still gotta feed the kids, still gotta be a good person.”