The Advot Project: Teaching teshuvah year-round

The High Holy Days are a time of reflection, forgiveness and teshuvah. “But what about the other months of the year?” asks Naomi Ackerman, founder of the Southern California-based nonprofit The Advot Project.

“Advot” means “ripples” in Hebrew. Ackerman said she chose the name when she established the organization in 2011 because “one small action can create a ripple effect of change.” For the past decade, Ackerman has used the program to teach healthy communication and relationship skills to youth ages 13-24. An established and acclaimed actress in her former home in Israel, Ackerman teaches these skills via theater exercises, role playing, writing prompts and games using puppets and masks.

She works with those who have had difficult home lives, are undocumented, have language barriers, have been incarcerated and/or have been involved gang violence. “There are so many ways of incarceration that isn’t (behind) bars,” she said. “How will they ever self-advocate if nobody is teaching them how to do that?”

Her programs also are designed to enable the students to make their own choices for the first time, and have agency over their lives.

“So many of these kids, you ask them where they want to be in 15 years and they say, ‘Alive,’ ” Ackerman said, “because they are surrounded by so much death. How amazing, if we go into community centers, into schools, the places (where they) don’t have possibility, and we can say, ‘You can create possibility. I believe in you. I’m going to show up every week.’ ”

Ackerman, together with her 12-person team of actors, musicians, social workers and communication leaders, enter juvenile detention and probation centers where they teach their 8- to 12-week programs. They work with Los Angeles County’s Camp Kenyon Scudder, Camp Joseph Scott, Camp David Gonzales, Camp Miller and HomeBoy Industries. They also visit schools and community centers including Fairfax High School, San Pedro High School and East Los Angeles Rising Youth Club, to name a few.

Just as an actor breaks down his or her character’s wants and needs in each scene of a play, Ackerman teaches her students how to break down and express their wants, needs and goals.

“You don’t say, ‘I’m sorry’ and then you have teshuvah. You say, ‘I’m sorry’ and the process begins. It’s the first step and so much has to come afterward.”— Naomi Ackerman

Ackerman’s career took a long and winding road before landing in Los Angeles and working with incarcerated youth. In Israel, she received a bachelor’s degree in education and theater from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, served in the Israel Defense Forces for two years and founded View Points, an Arab-Israeli dialogue theater group fostering coexistence through theater exercises and plays that reflected peace, communication, healthy relationship building and understanding.

“We would act out these extreme situations, almost grotesque,” Ackerman said. “We would laugh a lot but we would also think about ‘How can this be different?’ I started using my acting games to tackle these conversations of possibility, of racism, of lack of.”

She also created her acclaimed one-woman show, “Flowers Aren’t Enough,” which addresses domestic violence. To date, the show has been performed more than 1,900 times around the world and it has been translated into four languages. When she brought the show to high schools in the United States, the conversations after the performances turned into dialogues about healthy relationships and communication skills.

“It opened up this Pandora’s box,” Ackerman said. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, all my theater exercises were applicable here.’ ‘What’s my inner voice? ‘What’s my focus?’ Let’s use some gibberish.’ So many exercises we use are derived from character work.”

The early Advot Project curriculum was born out of that show. Initially, Ackerman performed “Flowers” and created a program around it in public high schools throughout Los Angeles. When her initial grant funding ran out, she connected with Camp David Gonzales, a boys’ juvenile delinquent facility in Malibu, where she pitched them a multi-week, arts-based theater program.

Despite being skeptical that “hardcore gang members” would want to wear wigs, play with puppets and participate in theater games, the administrators welcomed Ackerman.

“The guys leaned in,” Ackerman said. “They wore the wigs. They acted.”

When word got out that the participants’ behavior was changing for the better as a result of the program, facilitators, staff and other juveniles in the facility wanted to watch. With the participants’ approval, Ackerman decided to host a final presentation at the end of the program.

The boys final presentation celebration in Malibu. Photo courtesy of Naomi Ackerman.

“The camp got really into it,” she said, adding that the facility even bought the boys new polo shirts to wear during the performance. The kitchen made special snacks and Ackerman was able to bring in candy for everyone. “There was a feeling that they were being celebrated and their words were being celebrated … (I thought) if they were given reasons to feel worthy, maybe they wouldn’t end up here.” And, she said, it worked. By asking the students about their day, telling them they were loved and were worthy of love, changed their mindsets and allowed them to open up, not only during her program, but even after she left.

Three years after she began to work with boys and young men, Ackerman started to visit girls’ facilities. “When I went to the girls’ camps, my heart absolutely cracked open,” she said. A mother of three young girls, Ackerman said she couldn’t believe how young the girls in the detention centers were. Some were young moms themselves. “The boys had a lot of fun acting out scenarios and then we had discussions about it,” she noted, “but the girls acted out their pain.” She added that through those acting exercises, the girls received emotional validation and essential skill sets that helped change their thought processes and help them make different choices.

Over the course of six years, Ackerman standardized her programs and created Advot’s “pillars of communication.” Each class now ends with the mantra, “I am brave, I am confident and I am worthy,” and a final celebration presentation takes place at the end of every program.

Shawn LaRe’ Brinkley, vice president of The Advot Project board, said initially many participants don’t want to be there or don’t take the program seriously. “These kids come in tough,” she said, but Advot provides a safe, nonjudgmental zone.

“The Advot Project helps them to understand that there can be a future for them,” she continued. “I’m an African American woman. I have a vested interest in my community. The people that we serve are not necessarily Naomi’s (Jewish) community, but her heart is incredible. I think that she uses what she loves and what has brought her joy, to bring joy (to the kids), and a whole new understanding of what life can be to the population we serve.”

Photo courtesy of Naomi Ackerman.

Ackerman’s support for her “kids” extends beyond the classroom, and she forges relationships with many of them that began years ago and last to this day. She visits them on Thanksgiving and Christmas, brings snacks to sessions, hands out her cellphone number to those who get out of facilities so they have a person to call “outside of the walls.” She once drove to the Malibu detention center so she could obtain one of her student’s transcripts to re-enroll her in school. Ackerman loves these kids like they are her own. And she doesn’t expect you to. “What I do need,” she said, “is for everybody to care a little bit more.”

One of Ackerman’s success stories is Merced, now 22. When she came into the program at 14, she did so purely to get out of her cell for one hour a week. Merced said she was doubtful Ackerman could do anything for her. But Ackerman learned and remembered her name and told her college was a possibility. She finally won over Merced when Merced watched Ackerman intentionally intermingle different gangs during a session, and a fight broke out. Instead of panicking and calling a guard, Ackerman used communication and dialogue to resolve the situation.

“She wasn’t fazed by it,” Merced recalled. “I didn’t realize I didn’t know how to talk to people. I didn’t know it mattered how I felt. I also felt like a lot of us didn’t know how to express it to the people we cared about.”

Although she didn’t finish the Advot program, she did use the skills she learned in Ackerman’s classes to speak to her probation officer, and consequently was released early on good behavior. Two years later she used those same skills in front of her lawyer, a courtroom and judge, to obtain custody of her sister. She still speaks regularly with Ackerman to this day, and is now studying engineering at California Polytechnic State University.

“I love Merced like I love my kids,” Ackerman said. “I celebrate Merced, who is in college. That is extraordinary. There’s beauty in just having a regular life. Success is not going back to jail; having integrity; [and] giving back to the community.”

It’s success stories like Merced’s that fuel The Advot Project, said Program Director Annie Kee. “We don’t get case files on these students. They’re not relevant to the work. They have to do that work. I’m not there to give them permission to absolve themselves of all their sins. We don’t even use the words ‘good choice’ [or] ‘bad choice.’ We say, ‘What’s a different choice that would have led to something else?’ ”

Reuben, 19, began attending an Advot Project program through East Los Angeles Rising Youth Club last year. Both of his parents were hospitalized with COVID-19. He became the primary caretaker for his 7-year-old brother until his parents recovered. During that time, he pushed away his friends, felt burdened with school work and household duties, and didn’t speak to any of his co-workers. He said The Advot Project helped him process his emotions, communicate his needs, access tools for support and lean on new friends. “I don’t feel alone anymore,” he said. “I was so mad and sad. (The Advot Project) made me feel more comfortable so you can say anything. They help you grow.”

For Ackerman, this is the teshuvah that is “not so sexy but important. You don’t say, ‘I’m sorry’ and then you have teshuvah. You say, ‘I’m sorry’ and the process begins,” she said. “It’s the first step and so much has to come afterward.”

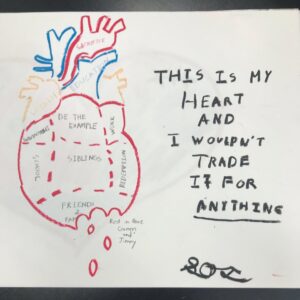

Artwork from one of the Advot Project sessions.

Yet despite the program’s success over the past decade, and providing thousands of youth with keys to open doors, not all the keys unlock all the doors, and not all the doors open. The day before a celebration for one of her HomeBoy youth summer programs, one of her students was killed in a gang-related shooting. “Sometimes (the gang) is stronger than them and it pulls them back,” Ackerman said.

She still struggles to create sustainable alumni programs for students so they are supported after they leave the detention centers. There was the Up and Out program, in which she would take a group of students to a restaurant and see a show once a month, and a Check-In program after that. Both were problematic because of complicated public transportation throughout Southern California, the fact that students aren’t all in one place anymore and they don’t always want to be contacted.

“No matter how many times I changed the program, I still reached out every time,” she said. “We call them, we text them, we feed them. It doesn’t work. We try again. That’s teshuvah.”

Ackerman’s Judaism goes hand-in-hand with her work. Teshuvah, she said, is knowing you are something and choosing to become something else. Her work, filled with small victories, reminds her that change is incremental and doesn’t have a single direction. While she loves the High Holy Days, she wrestles with the imagery that on Yom Kippur, the heavens close and nothing can be done beyond that point.

“In Judaism, you get a day to repent. At The Advot Project, it’s every day. Every day is an opportunity to change again. At The Advot Project, we are listening. I want the youth that we work with to know that even when the sky has closed and no one is there, things can change.”

To learn more about the Advot Project and its resources, visit the website.