L.A. Jewish filmmaker follows Arab and Israeli chefs working together in ‘Breaking Bread’

(Nof Atamna-Ismaeel in a scene from “Breaking Bread.” Credit: Cohen Media Group)

In Beth Elise Hawk’s documentary “Breaking Bread,” Israeli and Arab chefs team up to share, re-create and reinvent their family recipes. The mouthwatering fare, photographed in scrumptious detail, includes mussakhan, a Palestinian dish of sumac-infused chicken thighs, caramelized onions and laffa bread; taashimi, a whole fish baked in a crust; manti, a delicacy of savory lamb dumplings wrapped in a thin dough; and qatayef, a Palestinian dessert stuffed with cheese and pistachio nuts, traditionally eaten during Ramadan.

“Breaking Bread” has earned rave reviews on the film festival circuit and currently has a 100% positive rating on the review website Rotten Tomatoes.

Hawk’s Middle Eastern culinary journey began in 2015, when the former attorney for Walt Disney Studios was stuck in her car braving Los Angeles traffic. On the radio was an interview with microbiologist Nof Atamna-Ismaeel, who also was the first Palestinian Muslim to win Israel’s televised “Master Chef” cooking competition. In the interview, Atamna-Ismaeel spoke about using her celebrity status to establish the three-day A-Sham Arab Food Festival, which brings together Jewish and Arab chefs in the kitchen. The festival now takes place annually in the mixed Israeli-Arab city of Haifa. In “Breaking Bread,” Atamna-Ismaeel explains the festival is designed to move people beyond the Middle East conflict, stating, “I don’t believe there’s any room for politics in the kitchen.”

Levantine dessert. Credit: Cohen Media Group

After hearing that radio interview, Hawk contacted Atamna-Ismaeel on Facebook, where she learned that Atamna-Ismaeel was fluent in Arabic, Hebrew and English, serves on the board of the Peres Center for Peace and Innovation, where she creates culinary programs to foster communication between cultures, and raises funds for the Hillel Yaffe Medical Center in Hadera, which reaches out to Jewish and Arab communities.

In the documentary, Atamna-Ismaeel says that although she was raised in a Palestinian village, her parents sent her to a Jewish school. “It’s very hard to be an Arab inside Israel, because Palestinians consider you Israeli … and Israelis consider you Palestinian. You’re stuck in the middle. But people don’t understand that’s the best thing, [because] you can bridge both worlds.”

Hawk — who grew up eating Ashkenazi and French food in Montreal — said in a Zoom conversation with SoCal Jewish News she was immediately “obsessed and possessed” by Atamna-Ismaeel and her food festival. “I was so excited that this was a positive message coming from the Middle East. We rarely hear stories like this.” As a result, she decided to make her first feature-length documentary about Atamna-Ismaeel and her festival.

It’s very hard to be an Arab inside Israel, because Palestinians consider you Israeli … and Israelis consider you Palestinian. You’re stuck in the middle. But people don’t understand that’s the best thing, [because] you can bridge both worlds. — Nof Atamna-Ismaeel

Atamna-Ismaeel introduced Hawk to the 70 chefs from 35 restaurants that Hawk follows in the film. Among them are Shlomi Meir, a tattooed, chain-smoking, third-generation owner of Haifa’s Maayan Habira restaurant. A portrait of Meir’s late grandfather, who died when Meir was 16, hangs in a place of honor on the wall. Meir says he’s following in his Holocaust survivor grandfather’s footsteps. His grandfather lost his entire family in the Shoah, and reinvented himself as a restaurateur after immigrating to Israel.

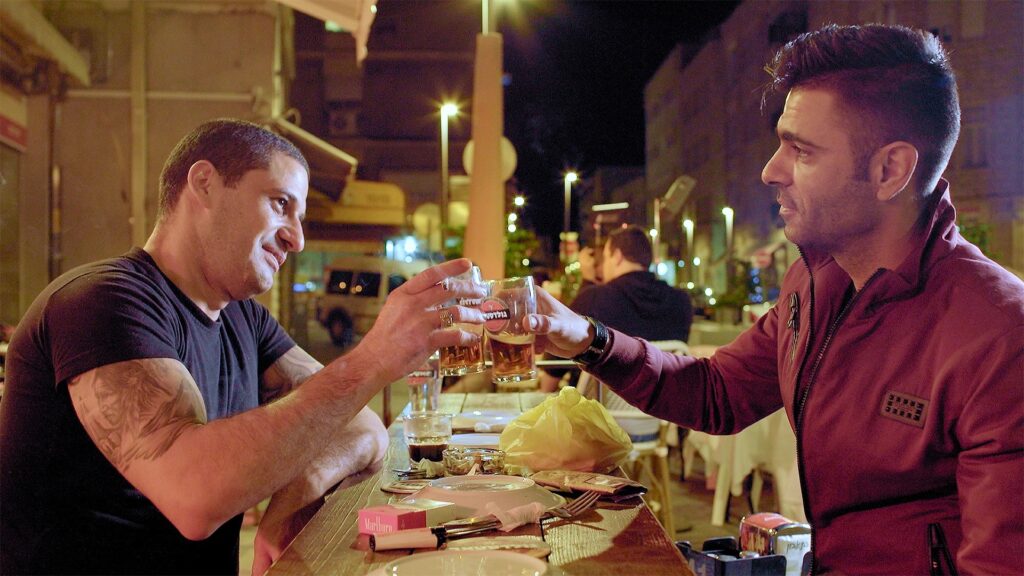

Chefs Shlomi Meir and Ali Khattib. Credit: Cohen Media Group

Meir continues his grandfather’s legacy by preparing the smoked meats and other strictly Ashkenazi recipes he brought to Haifa. Meir eschews including hummus on the menu and refuses to replace his grandfather’s antiquated refrigerator.

For the festival, Meir is paired with 27-year-old Arab chef Ali Khattib. Khattib’s culinary path was instilled in him by his Syrian-born grandmother, who cooked up unique dishes when he was growing up in the small northern Israeli town of Ghajar, which is split in two by the border between Israel and Lebanon. Khattib teaches Meir how to prepare his grandmother’s recipe for kishek, in which bulgur is soaked in yogurt for 20 days to create a soup. The two chefs spice up the dish by adding lamb to the mix.

Of Meir and Khattib, Hawk said, “They are mirror images. They recognize themselves in each other.”

The film also explores the collaboration between Osama Dalal, a Palestinian from the port city of Acre in northern Israel, and Ilan Ferron, who has a Jewish Italian mother, a French Catholic father, fiery red hair, matching beard and a blunt attitude. “I don’t give a f— that [Dalal’s] an Arab,” Ferron says. “The only thing I give a f— about is creating art.”

Together, the chefs whip up Dalal’s octopus maqluba, which layers the protein with baked vegetables, rice, chickpeas and potatoes.

Manti (lamb dumplings). Credit: Cohen Media Group

Tomer Abergel, who hails from a Moroccan Jewish family, teams up with Arab chef Salah Cordi from Jaffa. They transform a Palestinian pastry filled with sweet cheese and nuts into a savory dish stuffed with spiced ground meat. Cordi says that in his childhood neighborhood, “We spoke in Arabic, we laughed in Hebrew, we cursed in Romanian and it was all sababa (slang for cool or OK).”

While some reviewers have noted the absence of chefs from the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the film, The New York Times noted that the movie’s “repeatedly offered notions that food is a common language … seem trite and perhaps overly optimistic.” A Times of Israel blogger called the movie “Pollyanna-esque” and “extremely naïve.”

Ilan Ferron and Osama Dalal prepare to flip octopus maqluba. Credit: Cohen Media Group

In response, Hawk said, “We’ve gotten an abundance of incredibly positive feedback and coverage from people who embraced the film’s message. I was compelled to share the story of the A-Sham festival because it was a positive story emanating from the region.”

And Hawk also opens her film with a pertinent quote from the late chef, author and travel documentarian Anthony Bourdain: “Food may not be the answer to world peace, but it’s a start.”

“Breaking Bread” currently is playing at the Landmark Nuart Theatre, 11272 Santa Monica Blvd., Los Angeles, 90025. For tickets and information, click here.