Award-winning Israeli documentary explores the life and legacy of ‘the good Nazi’ Albert Speer

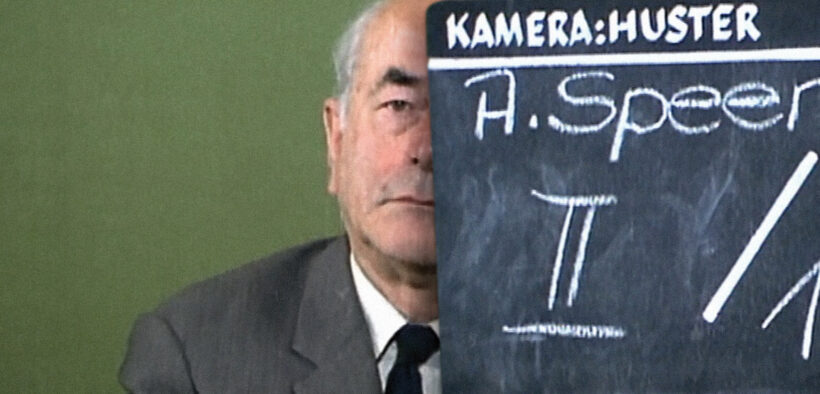

Photo: Albert Speer. Credit: Realworks LTD.

Seven years ago, Israeli filmmaker Vanessa Lapa initially wanted nothing to do with what would become her new documentary, “Speer Goes to Hollywood,” which won the 2021 Ophir Award (the Israeli version of the Oscars) for best documentary. The film exposes the postwar lies propagated by Hitler’s top architect, close friend and minister for armaments and war production, Albert Speer (1905-1981).

Lapa had just released her 2014 documentary “The Decent One,” which spotlights another war criminal — Heinrich Himmler — who orchestrated the Final Solution (the Nazi plan to kill the Jews of Europe). Helming that film had been soul-killing, Lapa told SoCal Jewish News in a recent Zoom interview from Berlin. “I didn’t want to go there again,” she said.

However, after a screening of “The Decent One” at New York’s Film Forum in 2014, Lapa was approached by an attorney, Stanley Cohen, who had purchased the English-language rights to Speer’s bestselling 1970 memoir, “Inside the Third Reich.” Cohen hoped Paramount Pictures might be interested in a feature film based on the blockbuster. In his book, the glib, charming Speer attempts to minimize his crimes and to create a myth about himself as the “good” Nazi.

According to screenwriter Andrew Birkin — who was hired to write a screenplay based on Speer’s memoir in 1971 — the project initially was turned down by the late film director Stanley Kubrick because he felt Speer would continue to deny his knowledge of the Holocaust when the film opened; he didn’t think a Jewish director should make a movie about a Nazi; and he was already preparing to direct his 1971 film, “A Clockwork Orange.”

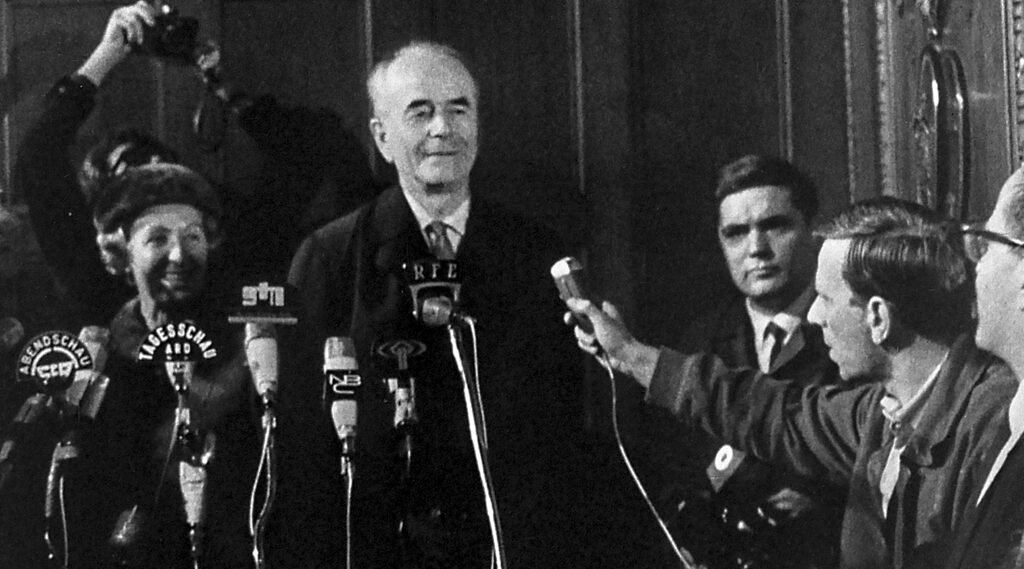

Speer at the Nuremberg Trials. Credit Realworks LTD

Lapa said she politely declined Cohen’s requests even though he regularly emailed her over the next eight months. “I told him it was not possible. I had this gut feeling that he would [pitch] me something I could not say ‘no’ to … [And] I didn’t want any more Nazis in my life.”

But Lapa’s fellow producer and sound designer, Tomer Eliav, surprised her by arranging a meeting with Cohen. Cohen told Lapa how producers had asked Birkin — a protégé of Kubrick’s and then in his mid-20s — to write the script. Birkin spent 3 1/2 months interviewing Speer at Speer’s home in a bucolic area near Heidelberg, where, having made millions from the sale of his book, Speer was living like a country gentleman.

Cohen then asked Lapa if she would be interested in making a documentary based on Birkin’s information. Learning Birkin had recorded more than 40 hours of never-published interviews with Speer, Lapa said, “After five minutes of listening to the cassette tapes, I understood that my gut feeling had been correct and I could not say ‘no’ to a documentary. I felt a combination of curiosity, a desire to face the challenge and the responsibility that this is something the world should know about.”

“I came to this project thinking of Speer as an opportunist trapped by the circumstances of Germany in the early 1930s. I had yet to know him as the liar and relentless manipulator that I eventually found in the tapes.” — Vanessa Lapa

Listening to the tapes, Lapa noted that Birkin wanted people to identify Speer as the hero of the story within the first five minutes of the film. As in his memoir, Speer continued to whitewash his wartime deeds and expressed the kind of carefully calculated regret that had saved him from the gallows at the Nuremberg Trials (making him the highest-ranking war criminal to escape the hangman). Among Speer’s claims: He was unaware that more than one third of his 12 million slave laborers had died of starvation, torture or other maltreatment. Instead, he blamed Hitler’s minister of labor, Fritz Sauckel, for their deaths.

Speer also claimed that he was simply an impressionable young man who wanted to help the German people, and that he had never visited a concentration camp and didn’t know about the Final Solution.

Speer received only a 20-year sentence at Berlin’s Spandau Prison. During that time, he jotted down bits of his memoir on napkins and convinced sympathetic guards to smuggle them out. When he died in 1981 at 76, his good reputation remained fairly intact.

Speer following his release from Berlin’s Spandau prison in 1966. Credit: RBB

“I came to this project thinking of Speer as an opportunist trapped by the circumstances of Germany in the early 1930s,” Lapa wrote in her director’s statement. “I had yet to know him as the megalomaniacal architect who wanted to build buildings that would last ‘forever,’ or as the liar and relentless manipulator that I eventually found in the tapes. In some ways, I was under his sway.”

As Lapa perused more than 47 visual and nine audio archives, she continued to feel “discomfited” and “unnerved” by the mounting evidence that Speer had denied his crimes in an attempt to “walk away like a saint from Sodom.”

For the visuals, she selected rare material that contradicts Speer’s version of events including Nuremberg testimony from a French-speaking survivor who distinctly recalls seeing Speer at the Mauthausen concentration camp.

Lapa grew up in a Zionist home in Antwerp, Belgium, among grandparents and other relatives whose families had died in Auschwitz or Dachau. One family member had been a Sonderkommando in Birkenau — a prisoner forced to herd Jews into the gas chambers and to burn their bodies in the crematoria.

Lapa made aliyah at 19. “I didn’t want to have much to do with the Holocaust, its victims and the Nazis,” she said. “I was trying to get away from 19 years in Belgium of hardcore Holocaust heritage.” Instead, she worked as a TV journalist, producing and directing more than 100 news pieces.

Speer with the SS in Belgium. Credit: Walter Frentz Collection Berlin.

But by the 2000s, she was unfulfilled with her job at Israel’s Channel 10, which, she felt, focused too much on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Switching gears, she spent two years at Camera Obscura, a cinema school in Tel Aviv.

In 2014, a professor at Tel Aviv University told her about a collection of unpublished diaries written by Himmler. “He didn’t reveal exactly how he got them,” Lapa said. “What interested me was [Himmler’s] degree of evil and where it came from.”

Listening to Birkin’s tapes of Speer, Lapa “felt shocked. I had the chills … Speer would have done anything that promoted Albert Speer. I was so terribly disgusted by him. I thought, ‘Is this how you’re trying to convince us you don’t feel any guilt?’ I’d get stuck for hours on certain sections and I couldn’t sleep.”

Lapa and Eliav chose to use only preexisting materials, with no narration, talking heads or new footage. “That allows the audience to feel that they are in the middle of a scene,” Eliav said, adding that because of the poor quality of Birkin’s recordings, he hired actors to voice the content verbatim, making sure each performer came from the same region and spoke with the same accent as the subjects.

Filmmaker Vanessa Lapa. Credit: Aline Frisch

Did Birkin go easy on Speer during his recording sessions? Lapa suggested Birkin was young and perhaps naïve. “Today he thinks he could’ve done better,” she said. (Read the interview with Birkin and his objections to Lapa’s film here.)

Lapa said she has been profoundly affected by making the film. “I’ve lost even more faith in humanity,” she said. “It took an emotional toll.”

“Speer Goes to Hollywood” will have online screenings at dates to be determined, and also will be available on video-on-demand. For more information, visit www.speergoestohollywood.com.